Somerdale to Skarbimierz

James Meek in London Review of Books:

How to explain Poland’s swing against the European Union? How to explain the election of the Catholic fundamentalist, authoritarian, populist, Eurosceptic Law and Justice Party to rule a booming country that has benefited from more than €130 billion in EU investment in its roads, railways and schools, a country where only a few years after EU accession in 2004 hundreds of foreign factories and distribution centres opened, employing hundreds of thousands of people, a country whose citizens have taken advantage of EU freedom of movement to travel, work and study across the continent in their millions?

Human Theory of the Left

Eliezer Yudkowsky on Facebook, so quoted in it’s entirety here for posterity:

Bryan Caplan’s Simplistic Theory of Left and Right says “The Left is anti-market and the Right is anti-Left”. This theory is half wrong, and will for this reason confuse the Left in particular. It ought to be a clue that if you ask the Left whether they’re anti-market, most of the Left will answer, “Of course not,” whereas if you ask the Right whether they’re anti-Left, they’ll answer “Hell yes we are.” People may understand themselves poorly a lot of the time, but they often know what they hate.

My “Human Theory of the Left” is as follows: The Left holds markets to the same standards as human beings.

Consider a small group of 50 people disconnected from the outside world, as in the world where humans evolved. When you offer somebody fifty carrots for an antelope haunch, that price carries with it a great array of judgments and considerations, like whether that person has done you any favors in the past, and how much effort it took them to hunt the antelope, and how much effort it took you to gather the carrots. If you offer them an unusually generous price, you’d expect them to give good prices in return in the future. A low price is either a status-lowering insult, or carries with it a judgment that the other person already has lower status than you.

And that’s what the Left sees when they look at somebody being paid $8/hour. They don’t see a supply curve, or a demand curve; or a tautology that for every loaf of bread bought there must be a loaf of bread sold, and therefore supply is always and everywhere equal to demand; they don’t see a price as the input to the supply function and demand function which makes their output be equal. They see a judgment about how hard an employee works, and how much they need and deserve.

So of course they hate whatever looks at a poor starving mother and says “$8/hour”. Who wouldn’t?

Ask them and they’ll tell you: They don’t hate markets. They just think that the prices and outcomes aren’t fair, and that tribal action is required for everyone to get together and decide that the prices and outcomes should be fairer.

If this post gets shared outside my own feed, some people will be reading this and wondering why I wouldn’t want prices to be fair.

And they’ll suspect that I must worship the Holy Market and believe its prices to be wise and fair; and that if I object to any regulation it’s because I want the holy, wise and fair Market Price to be undisturbed.

This incidentally is what your non-economist friends hear you saying whenever you use the phrase “efficient markets”. They think you are talking about market prices being, maybe not fair, but the most efficient thing for society; and they’re wondering what you mean by “efficiency”, and who benefits from that, and whether it’s worth it, and whether the goods being produced by all this efficiency are actually flowing to the people making $8/hour.

You reply, “What the hell that is not even remotely anything the efficient markets hypothesis is talking about at all, you’re not even in the right genre of thoughts, the weak form of the EMH says that the supply/demand-intersecting price for a highly-liquid well-traded financial asset is a rational subjective estimate of the expectation of its supply/demand-intersecting price two years later taking into account all public information, because otherwise it would be possible to pump money out of the predictable price changes. The EMH is a descriptive statement about price changes over time, not a normative statement about the relation of asset prices to anything else in the outside world.”

This is not a short paragraph in the standard human ontology.

“So you think that $8/hour wages are efficient?” they say.

“No,” you reply, “that’s just not remotely what the word efficient means at all. The EMH is about price changes, not prices, and it has nothing to do with this. But I do think that $8/hour is balancing the supply function and the demand function for that kind of labor.”

“And you think it’s good for society for these functions to be balanced?” they inquire.

The one is willing to consider the force of the argument they think they’re hearing–that the market is a weird and foreign god which will nonetheless bring us the right benefits if we make it the right sacrifices. But, they respond, is the market god really bringing us these benefits? Aren’t some people getting shafted? Aren’t some people being sacrificed to save others, maybe a lot of people being sacrificed to save a few others, and isn’t that worth the tribe getting together and deciding to change things?

And you clutch your hair and say, “No, you don’t get it, you know the market is doing something important but you don’t understand what that thing is, you think the markets are like arteries carrying goods around and they can get blocked and starve some tissues, and you want to perform surgery on the arteries to unblock them, but actually THE MARKETS ARE RIBOSOMES AND YOU’RE TRYING TO EDIT THE DNA CODE AND EVERYTHING WILL BREAK SIMULTANEOUSLY LIKE IT DID IN VENEZUELA.”

And what they hear you saying is “The markets are wise, and their prices carry wisdom you knoweth not; do you have an arm like the Lord, and can your voice thunder like His?”

Because, they know in their bones, when a corporation pays an employee $8/hour, it means something. It means something about the employer and it says something about what the employer believes about the employee. And if you say “WAIT DON’T MESS WITH THAT” there’s a lot of things you might mean that have short sentences in their ontology: you could mean that you believe $8/hour is the fair price; you could mean you believe the price is unfair but that it’s worth throwing the employees under the bus so that society keeps functioning; you could believe that maybe the market knows something you don’t.

And all of those things, one way or another, are saying that you believe there’s some virtue in that $8/hour price, some virtue transmitted to it by the virtue you think is present within the market that assigns it. And that’s a cruel thing to say to someone getting $8/hour, isn’t it?

Just look at what the market does. How can you believe that it’s wise, or right, or fair?

And they can’t believe that you don’t think that–even though you’ll very loudly tell them you don’t think that–when you are being like “IF YOU WANT THEM TO HAVE MORE MONEY THEN JUST GIVE THEM MONEY BUT FOR GOD’S SAKE DON’T MESS WITH THE NUMBER THAT SAYS 8.”

This by the way is another example of why it’s an important meta-conversational principle to pay a lot of attention to what people say they believe and want, and what they tell you they don’t believe and want. And that if nothing else should give you pause in saying that the Left is anti-market when so many moderate leftists would immediately say “But that’s not what I believe!”

Maybe we’d have an easier time explaining economics if we deleted every appearance of the words “price” and “wage” and substituted “supply-demand equilibrator”. A national $15/hour minimum supply-demand equilibrator sounds a bit more dangerous, doesn’t it? Increase the Earned Income Tax Credit, or better yet use hourly wage subsidies. Establish a land value tax and give the money to poor people, while being careful not to establish new paperwork requirements that exclude busy or struggling people and being careful about phaseout thresholds. Or if you really insist on looking at things in the simplest possible way, then take money away from rich people and give it to poor people. It’ll do less damage than messing with the supply-demand equilibrators.

I feel like I’m at a banquet watching people trying to eat the plates and they’re like “No, no, I understand what food does, you’re just not familiar with the studies showing that eating small amounts of ceramic doesn’t hurt much” and I’m like “If you knew what food does and what the plates do then you would not be TRYING to eat the plates.”

I honestly wonder if we’d have better luck explaining economics if we used the metaphor of a terrifying and incomprehensible alien deity that is kept barely contained by a complicated and humanly meaningless ritual, and that if somebody upsets the ritual prices then It will break loose and all the electrical plants will simultaneously catch fire. Because that probably is the closest translation of the math we believe into a native human ontology.

Want to help the bottom 30%? Don’t scribble over the mad inscriptions that are closest to them, trying to prettify the blood-drawn curves. Mess with any other numbers than those, move money around in any other way than that, because It is standing very near to them already.

People like Bryan Caplan see people in 6000BC wearing animal skins as the native state of affairs without the Market. People like Bryan keep trying to explain how the Market got us away from that, hoping to foster some good feelings about the Market that will lead people to maybe have some respect for its $8/hour figure.

If my Human Theory of the Left is true, then this is exactly the wrong thing to say, and eternally doomed to failure. To praise that which would offer $8/hour to a struggling family, is directly an insult to that family, by the humanly standard codes of honor. If you want people to leave the $8/hour price alone, and you want to make the point about 6000BC, you could maybe try saying, “And that’s what Tekram does if you have no price rituals at all.”

But don’t try to tell them that the Market is good, or wise, or kind. They can see with their own eyes that’s false.

Some good discussion in the comments, including from Caplan.

Federalism in Blue and Red

Are you a liberal that lives in a rich blue state? Do you look down on red states that cut services as they cut taxes? Perhaps you should check your privilege, and read this excellent article by Joshua T. McCabe on fiscal capacity in National Affairs:

In 2012, Republican governor Sam Brownback and the Republican state legislature in Kansas undertook what would soon be characterized as a radical experiment in supply-side economics. Over the following several years, they reduced the state’s progressive income tax from a top rate of 6.45% down to 4.6% and essentially raised the state’s sales tax from 5.7% to 6.5%. Grover Norquist and Art Laffer were ecstatic while liberals predicted gloom and doom. Five years later, as revenues plunged and the legislature scrambled to find enough money to fund schools and basic services, liberal pundits around the country let out a collective “I told you so.”

Meanwhile, few people noticed that analogous changes were underway in true-blue Massachusetts. In 2009, Democratic governor Deval Patrick and the Democratic state legislature likewise raised the state’s sales tax from 5% to 6.25%. Over the following several years, that same legislature — but with Republican governor Charlie Baker — reduced the state’s flat income tax from 5.3% to 5.1%. Despite strikingly similar shifts in its tax structure, Massachusetts received essentially no praise from supply-side evangelists or condemnation from liberal pundits. More important, no budget crisis followed. What explains these divergent outcomes following similar tax reforms?

Libertarian Social Engineering

Jason Kuznicki at Cato Unbound:

To my mind there are two ways to do libertarian activism.

One approach is easy, deeply satisfying, and - at least on our current margin - it’s basically ineffective. The other approach is difficult, usually thankless, and - I dare say it - revolutionary when it works.

Let’s call the first way libertarian moralizing. We know it by what it aims to produce: The intended product is more libertarians. Eventually we’ll persuade everyone, or at least enough of everyone, and then we’ll change the world.

[…]

To pick a completely incendiary name, I will call this second type of activism libertarian social engineering. By this I mean the deliberate attempt to create, on an incremental, case-by-case basis, the new, voluntary institutions and practices that a society would need if it were to become significantly more private, more decentralized, and more free. I mean here institutions like cryptocurrency, which is already well known; private institutions of assurance and trust in consumer satisfaction and safety; and Alexander Tabarrok’s idea of the Dominant Assurance Contract, which is exceptionally obscure, but which stands to my mind a fair chance of making almost all state action obsolete.

How American Politics Went Insane

Jonathan Rauch in The Alantic:

Chaos syndrome is a chronic decline in the political system’s capacity for self-organization. It begins with the weakening of the institutions and brokers—political parties, career politicians, and congressional leaders and committees—that have historically held politicians accountable to one another and prevented everyone in the system from pursuing naked self-interest all the time. As these intermediaries’ influence fades, politicians, activists, and voters all become more individualistic and unaccountable. The system atomizes. Chaos becomes the new normal—both in campaigns and in the government itself.

Our intricate, informal system of political intermediation, which took many decades to build, did not commit suicide or die of old age; we reformed it to death. For decades, well-meaning political reformers have attacked intermediaries as corrupt, undemocratic, unnecessary, or (usually) all of the above. Americans have been busy demonizing and disempowering political professionals and parties, which is like spending decades abusing and attacking your own immune system. Eventually, you will get sick.

Not about directly about Tump, written early last year. Pointing out a lot of the cronyism and other regressive structures in politics may have helped the whole system function better. But which direction forward, change our political system, or go back to how it was?

Welcome to Poppy’s World

Lexi Pandell at Wired:

It’s hard to explain Poppy to the uninitiated. But I’m going to try.

Let’s start with the edge of the Poppy rabbit hole: You see a woman in a YouTube video. She is blond and petite with the kind of Bambi-sized brown eyes you rarely encounter in real life. She seems to be in her late teens or early twenties, though her pastel clothing and soft voice are much more childlike.

Maybe you start with “I’m Poppy,” a video where she repeats that phrase over and over in different inflections for 10 minutes. That’s right. Ten minutes. She seems, by turns, bored, curious, and sweet. As it continues, you notice that her voice does not quite match the movement of her lips; it’s delayed just a beat.

You watch more. There’s a video of her interviewing a basil plant.

And two of her reading out loud from the Bible. In one, her nose spontaneously starts bleeding. All of her videos are like this: unsettling, repetitive, sparse. Imagine anime mixed with a healthy heap of David Lynch, a dash of Ariana Grande, and one stick of bubblegum.

The Anarchist in the Woodshop

Daniel D. Clausen discusses Christopher Schwarz’s work at Lost Art Press:

[The Anarchist’s Design Book] explains, again in narrative form, how to make that kind of simple furniture. With more or less the same basic set of flea market tools in the Anarchist’s Tool Chest, along with a willingness to try, experiment, fail, and try again, Schwarz shows that most people can turn out simple, functional furniture. And it will be better made than what is available flat packed from local box stores, and at a fraction of the price of antiques or what handmade furniture costs. Since crafts people have to make a living building something like a chair a week, if they are quick, that sort of production will never be democratically available. It is cost prohibitive for all but the wealthy, and always will be. (This critique, also leveled at William Morris’s Arts and Crafts movement—that the laborers were making furniture for the rich and thus failing at the Marxist goal of revolution—has never struck me as very damning. There has to be some mechanism to get money from where the money currently is, and we ought to be forgiven if we prefer this one to violence.)

The larger political argument in these “anarchist” books is that in a society structured by late consumer capitalism, we’ve all sold our birthright to making things for the bowl of pottage that is IKEA bookshelves and meaninglessness. It’s an appealing argument for direct action, not just in politics, but in daily material life.

The surprise success of Schwartz’s books prompts some questions: What conditions is Lost Art Press responding to? And why has this response been so successful?

The conditions, obviously, are the same ones that suffuse our political moment. Sit down to actually read Karl Marx and it will be difficult not to grant that his analysis of the conditions of capitalism, if not his rather nebulous prescriptions, are prescient. His labor theory of value is appealing, especially to those who have skill in making things. The concentration of capital, high barriers to entry, and economies of scale with diminishing returns all work against the “petite bourgeois” craftsman.

Gonwild - Euclidean Good Time

I discovered a new part of the internet today:

Gonwild is a place for closed, Euclidean Geometric shapes to exchange their nth terms for karma; showing off their edges in a comfortable environment without pressure.

Dave at Bees and Bombs is pretty great:

and not so gemetric, but very artistic:

Farewell - ETAOIN SHRDLU

A film created by Carl Schlesinger and David Loeb Weiss documenting the last day of hot metal typesetting at The New York Times.

“It’s inevitable that we’re going to go into computers, all the knowledge I’ve acquired over these 26 years is all locked up in a little box called a computer, and I think most jobs are going to end up the same way. [Do you think computers are a good idea in general?] There’s no doubt about it, they are going to benefit everybody eventually.”

–Journeyman Printer, 1978

Hanging On For Dear Life

At Biophilia:

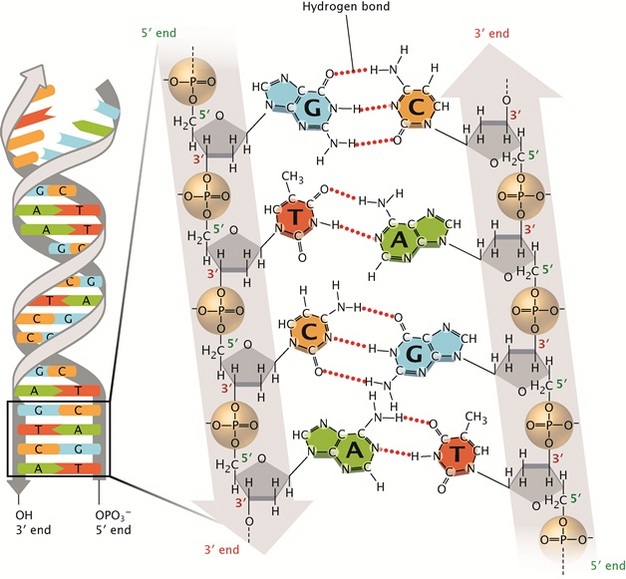

At the very heart of our hereditary and developmental lives is DNA synthesis- replication that copies one duplex into two. But each beautiful, classic DNA duplex has two strands, each of which needs to be copied. Not only that, but those two strands go in opposite directions. The one is the complement, or anti-sense, of the other one, and in chemical terms heads the other way. This creates a significant problem, since the overall direction of replication can only go one way- the direction of the fork where the parental duplex splits into two.

Inside the world’s biggest trivia competition

Owen Phillips in The Outline:

It was a Friday evening on the first T-shirt weather weekend of the year, but almost everyone in the small city of Stevens Point, Wisconsin, was indoors. Families and friends hunkered down in basements or camped out in attics. Stores on Main Street were shuttered, black-out curtains hung in the windows. And everyone’s radio was tuned to the local college station, 90FM, where question after question was being read live over the air.

The occasion was the start of an annual tradition in Stevens Point: Trivia, the self-proclaimed world’s biggest trivia contest, in which thousands of players compete on hundreds of teams to answer eight questions every hour, for 54 hours straight.

A John Bates Clark Prize for Economic History

Kevin Bryan discusses the work of Dave Donaldson:

A canonical example of Donaldson’s method is his most famous paper, written back when he was a graduate student: “The Railroads of the Raj”. The World Bank today spends more on infrastructure than on health, education, and social services combined. Understanding the link between infrastructure and economic outcomes is not easy, and indeed has been a problem that has been at the center of economic debates since Fogel’s famous accounting on the railroad. Further, it is not obvious either theoretically or empirically that infrastructure is good for a region. In the Indian context, no less a sage than the proponent of traditional village life Mahatma Gandhi felt the British railroads, rather than help village welfare, “promote[d] evil”, and we have many trade models where falling trade costs plus increasing returns to scale can decrease output and increase income volatility.

Donaldson looks at the setting of British India, where 67,000 kilometers of rail were built, largely for military purposes.

The Future of Not Working

Annie Lowrey talks UBI via the charity GiveDirectly in The New York Times:

If you’re hungry, you cannot eat a bed net. If your village is suffering from endemic diarrhea, soccer balls won’t be worth much to you. “Once you’ve been there, it’s hard to imagine doing anything but cash,” Faye told me. “It’s so deeply uncomfortable to ask someone if they want cash or something else. They look at you like it’s a trick question.”

A Model of Technological Unemployment

There is a bit of a backlash against UBI in the economics community at the moment, which I think is unfortunately due to a lack of awareness of potential changes to the labor market coming. Here is a paper by Daniel Susskind talking about why mainstream economics may have it wrong on the labor issues:

The economic literature that explores the consequences of technological change on the labour market tends to support an optimistic view about the threat of automation. In the more recent ‘task-based’ literature, this optimism has typically relied on the existence of firm limits to the capabilities of new systems and machines. Yet these limits have often turned out to be misplaced. In this paper, rather than try to identify new limits, I build a new model based on a very simple claim – that new technologies will be able to perform more types of tasks in the future. I call this ‘task encroachment’. To explore this process, I use a new distinction between two types of capital – ‘complementing’ capital, or ’c-capital’, and ‘substituting’ capital, or ‘s-capital’. As the quantity and productivity of s-capital increases, it erodes the set of tasks in which labour is complemented by c-capital. In a static version of the model, this process drives down relative wages and the labour share of income. In a dynamic model, as s-capital is accumulated, labour is driven out the economy and wages decline to zero. In the limit, labour is fully immiserated and ‘technological unemployment’ follows.

Personally I see huge changes coming in the near to medium term (5-40 years), such by the end of that about 40% of currently employed population will have no jobs available to them. (If minimum wage laws hold, that would be literately no jobs, if minimum wage laws fall, then it means jobs that pay only sustenance level). That will cause major changes to the economy of course. Goods will be produced at much lower cost, but how will people who don’t have jobs buy them? This is where UBI begins to make sense to me.

Then in medium to long term we have the potential of AI singularity, in which case, who knows. Even if no singularity, the automation encroachment on refuge labor will continue …

Via MR.

A New Progressive Federalism

The new dean of Yale Law has some smart things to say about federalism:

Heather Gerken in Democracy:

Progressives are deeply skeptical of federalism, and with good reason. States’ rights have been invoked to defend some of the most despicable institutions in American history, most notably slavery and Jim Crow. Many think “federalism” is just a code word for letting racists be racist. Progressives also associate federalism—and its less prominent companion, localism, which simply means decentralization within a state—with parochialism and the suppression of dissent. They thus look to national power, particularly the First and Fourteenth Amendments, to protect racial minorities and dissenters from threats posed at the local level.

But it is a mistake to equate federalism’s past with its future. State and local governments have become sites of empowerment for racial minorities and dissenters, the groups that progressives believe have the most to fear from decentralization. In fact, racial minorities and dissenters can wield more electoral power at the local level than they do at the national. And while minorities cannot dictate policy outcomes at the national level, they can rule at the state and local level. Racial minorities and dissenters are using that electoral muscle to protect themselves from marginalization and promote their own agendas.

Also in Vox:

Federalism doesn’t have a political valence. These days it’s an extraordinarily powerful weapon in politics for the left and the right, and it doesn’t have to be your father’s (or grandfather’s) federalism. It can be a source of progressive resistance — against President’s Trump’s policies, for example — and, far more importantly, a source for compromise and change between the left and the right. It’s time liberals took notice.

Staying true to principle in the age of Trump

Ilya Somin in the WaPo:

Wall Street Journal columnist Bret Stephens, a prominent conservative opponent of Trump, recently noted that he is now more popular on the left than in the past, but despised by many of his former fans on the right:

Watching this process unfold has been particularly painful for me as a conservative columnist. I find myself in the awkward position of having recently become popular among some of my liberal peers—precisely because I haven’t changed my opinions about anything.

Won’t directly apply to many of you, being liberals. But, please read this well written mini essay about the detrimental effects of partisan bias, and reflect on it now, when it doesn’t apply, so that later when it does perhaps you can be a better participant, holding to your values no matter who is leading your team.

Winners of the 2017 World Press Photo Contest

World Press Photo 2017, a must read as always.

General News, First Prize, Singles—Offensive On Mosul: Iraqi Special Operations Forces search houses of Gogjali, an eastern district of Mosul, looking for Daesh members, equipment, and evidence on November 2, 2016. The Iraqi Special Operations Forces, also known as the Golden Division, is the Iraqi unit that leads the fight against the Islamic State with the support of the airstrikes of the Coalition Forces. They were the first forces to enter the Islamic State-held city of Mosul in November of 2016.

Laurent Van der Stockt / Getty Reportage for Le Monde

And the series on Iran is great.

How Do I Crack Satellite and Cable Pay TV?

If you are intrested in hardware reverse enginereering in crypto systems, this is a very accessable talk.