Things tagged film:

The evolution of pace in popular movies

James E. Cutting (name checks out):

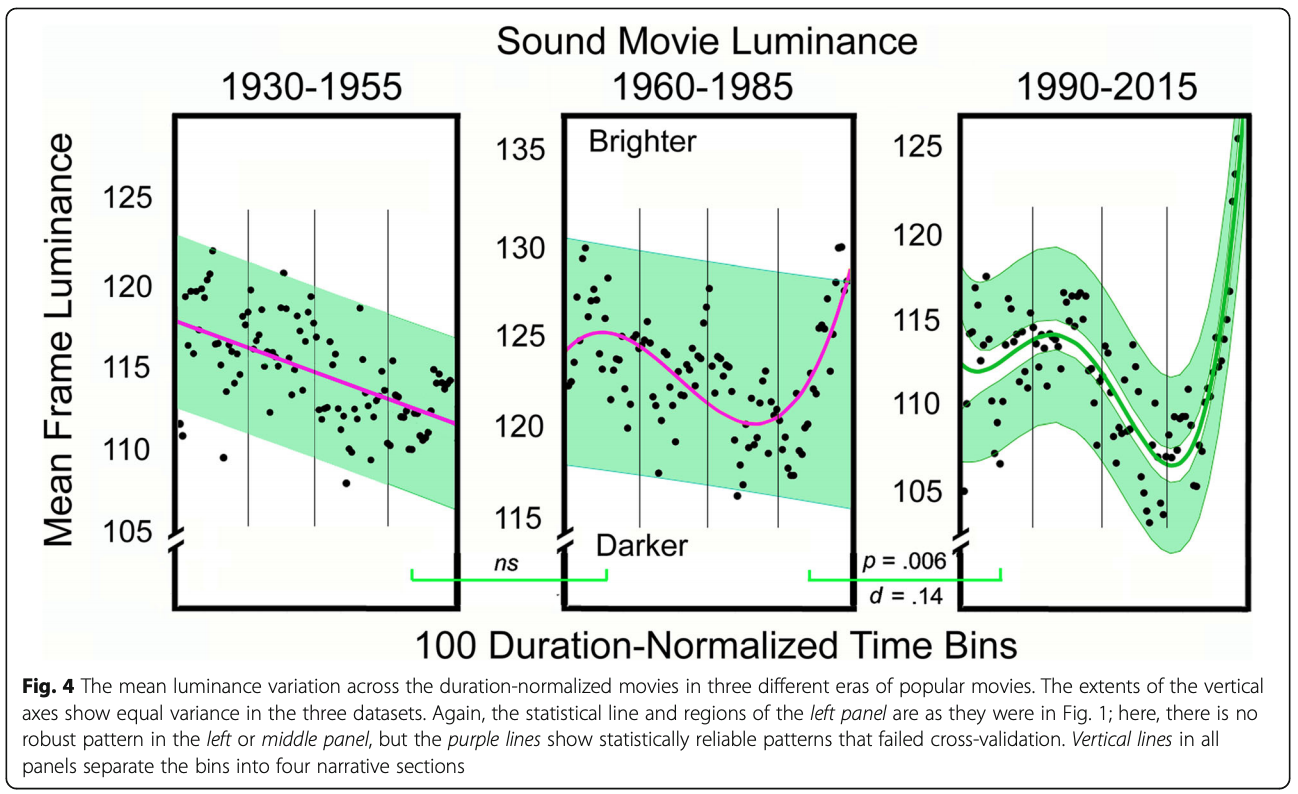

Movies have changed dramatically over the last 100 years. Several of these changes in popular English-language filmmaking practice are reflected in patterns of film style as distributed over the length of movies. In particular, arrangements of shot durations, motion, and luminance have altered and come to reflect aspects of the narrative form.

Stanley Kubrick's Boxes

Unfortunately the full copy is no longer on Vimeo.

Via Kottke, more info there.

Start thinking with your head instead of your hips

Start thinking with your head instead of your hips

– Sidney Falco “Sweet Smell of Success” (1957)

Display Prep Demo

A cinematographer makes an attempt to preform a digital vs. film comparison. In a very particular way. I think he fails to reach the goal he set out for himself, but I don’t believe that the theory he presents is incorrect. In a few years the iteration in digital imaging tech, and the math to preform the transforms will progress, and we will be there. Then this silly debate will be over :)

See also this revealing conversation he had with a film purist:

People are so religious about this that they’re resistant to even trying. But not trying does not prove it’s not possible.

If you believe there are attributes that haven’t been identified and/or properly modeled in my personal film emulation, then that means you believe those attributes exist. If they exist, they can be identified. If they don’t exist, then, well, they don’t exist and the premise is false.

It just doesn’t seem like a real option that these attributes exist but can never be identified and are effectively made out of intangible magic that can never be understood or studied.

To insist that film is pure magic and to deny the possibility of usefully modeling its properties would be like saying to Kepler in 1595 as he tried to study the motion of the planets: “Don’t waste your time, no one can ever understand the ways of God so don’t bother. You’ll never be able to make an accurately predictive mathematical model of the crazy motions of the planets — they just do whatever they do.”

Ensemble Staging

How do you emphasize to the audience that something is important? Well, you could always cut to a close-up, but how about something subtler? Today I consider ensemble staging — a style of filmmaking that directs the audience exactly where to look, without ever seeming to do so at all.

Fantantastic movie too (Memories of Murder), this should convince you to see it.

Via kottke.org

Damon Lindelof on Struggling With Depression and Why Knowing J.J. Abrams is "A Bit of a Curse"

Long interview with Damon Lindelof by Stephen Galloway, covers lots of ground, and gets to some intresting places:

LINDELOF: I had a dream in terms of what I wanted to achieve in my life, and when I got that call, it was so above and beyond anything that I had ever dreamed, that I felt I didn’t deserve it. And I was like, “I don’t deserve this, I’m not entitled to it, I haven’t earned it. What am I supposed to do with this?” And my wife and I would go out for breakfast on the weekends, even though I would go into the office afterwards, and we’d be sitting there, eating, and the people at the table next to us were talking about Lost. And I was like, this is not a normal thing that should be happening right now. And Heidi my wife was smiling, like, isn’t this the greatest thing in the world? And it was the worst thing in the world. And the fact that everybody was telling me that it should be great, made me feel like there was something wrong with me.

GALLOWAY: Thank you for talking about that, too. Because I think it’s important for people to know. Everybody thinks, “Oh, when I have success, my life is going to be perfect,” and that’s just not what life is.

LINDELOF: I’ll be honest with you, and I’m glad that you said that because there was a part of me prior to this happening where whenever someone who had achieved their dream, like an actor, was complaining, saying like “This isn’t easy,” I’d be like, “Oh come on.” You know, “Boo-hoo, Russell Crowe.”

LINDELOF: But if I can be completely and totally precious about it for a second, we are artsy folk, you know? I mean, we all fancy ourselves artists and we are wired as artists and part of being a good artist is tapping into some sort of emotional reality and trying to communicate it to others, through our art. And that requires a certain amount of vulnerability, and nakedness. And that’s hard. You know, if you’re doing it well, it’s really scary, and in order to do it well you have to make a lot of mistakes, and when you make mistakes you get scared. And it’s very hard for me to say I’m scared right now, or I’m sad, and fear and depression can sometimes manifest themselves as anger. Anger is not a real feeling. Every time in my life I’ve ever been angry, it’s because I was scared, or because I was sad and I didn’t know it. Like, anger doesn’t just come out of a vacuum.

Via NextDraft.

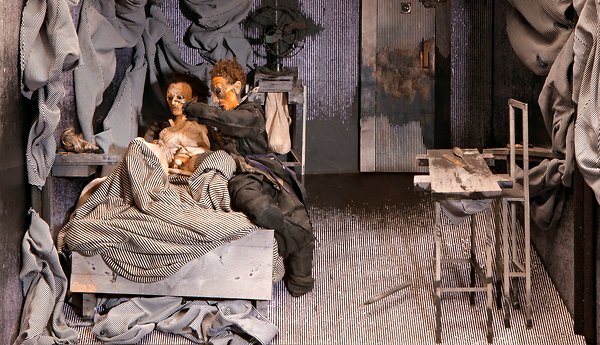

Film Forum - The Quay Brothers – On 35mm

In NYC, at the Film Forum.

American identical twins working in London, stop motion animators Stephen and Timothy Quay (born 1947 in Norristown, Pennsylvania) find their inspiration in Eastern European literature and classical music and art, their work distinguished by its dark humor and an uncanny feeling for color and texture. Masters of miniaturization, they turn their tiny sets into unforgettable worlds suggestive of long-repressed childhood dreams.

Bitter Lake

Adam Curtis’s beautiful, gripping film unravels a story of violence, bloodshed and bitter ironies. Beginning with a fateful meeting between President Roosevelt and King Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia, Curtis delves into a mass of historical archives to shed light on Afghanistan and the west.

The film was quite something. When I heard it was “found footage” I thought it was going to be something else. I still wish it had been that, but what it is still amazing. Definitely worth watching.

The Untold Story of ILM, a Titan That Forever Changed Film

Wired with an oral history of ILM:

No one wanted Star Wars when George Lucas started shopping it to studios in the mid-1970s. It was the era of Taxi Driver and Network and Serpico; Hollywood was hot for authenticity and edgy drama, not popcorn space epics. But that was only part of the problem.

As the young director had conceived it, Star Wars was a film that literally couldn’t be made; the technology required to bring the movie’s universe to visual life simply didn’t exist. Eventually 20th Century Fox gave Lucas $25,000 to finish his screenplay—and then, after he garnered a Best Picture Oscar nomination for American Graffiti, green-lit the production of Adventures of Luke Starkiller, as Taken From the Journal of the Whills, Saga I: The Star Wars. However, the studio no longer had a special effects department, so Lucas was on his own.

Insignificant Bullets, Evil Poachers, and L.A. Culture

Most of what we’ve heard about Werner Herzog is untrue. The sheer number of false rumors and downright lies disseminated about the man and his films is truly astonishing. Yet Herzog’s body of work is one of the most important in postwar European cinema.This conversation is excerpted from Werner Herzog: A Guide for the Perplexed, Paul Cronin’s volume of dialogues that provides a forum for Herzog’s fascinating views on the things, ideas, and people that have preoccupied him for so many years.

Werner is someone I tend to disagree with, on nearly everything I read of his. But I still love to hear his views, as they are very intilectual stimulating. And of course his films are amzing works of art. I do recomend the book.

Surely you can’t be serious: An oral history of Airplane!

We spoke with as many people involved in Airplane! as we possibly could—including the Zuckers, Jim Abrahams, and cast members Robert Hays, Frank Ashmore, Al White, Lee Bryant, Ross Harris, Jill Whelan, Maureen McGovern, David Leisure, Gregory Itzin, Marcy Goldman, and Jimmie Walker—and asked them to reflect on their experiences while making the film as well as their astonishment that audiences still love Airplane!

Jennifer Lawrence and Bradley Cooper in a dud: Why Serena went straight to video.

Adam Sternbergh in Slate:

Serena is a bracing reminder of how much expertise goes into making even the most uninspired movie—how dozens of people with wildly different skill sets all have to perform well or the whole project is imperiled. The stars may be the ones with their names plastered over the title, but if you’re Jennifer Lawrence, trapped in Serena like Rapunzel in her tower dungeon, your powers of self-salvation are limited. You can’t reedit the film or rescore its music or rescout its locations. In the end, the lesson of Serena isn’t how remarkable it is when a movie like this goes badly, but how improbable it is that any movie at all turns out to be good.

David Fincher - And the Other Way is Wrong

Tony Zhou Every Frame a Painting:

For sheer directorial craft, there are few people working today who can match David Fincher. And yet he describes his own process as “not what I do, but what I don’t do.” Join me today in answering the question: What does David Fincher not do?

Moments That Changed The Movies: Jurassic Park

A look back at Jurassic Park, the groundbreaking decision to create digital dinosaurs, and the impact it had on the future of movies.

ARST ARSW: Star Wars sorted alphabetically

All of the English dialogue in “Star Wars”, split into words, and sorted alphabetically.

Aug(De)Mented Reality

Using a unique animation technique involving traditional animation cels and his iphone 5s, Hombre_mcsteez turns everyday life into an odd creature infested cartoon universe.

LIFT

Filmmaker Marc Isaacs sets himself up in a London tower block lift. The residents come to trust him and reveal the things that matter to them creating a humorous and moving portrait of a vertical community.

Quay Brothers Retrospective at MoMA

Roberta Smith in the NYT:

Not all filmmakers create complete and resonant fantasy worlds, rife with strange, sometimes frightening beings as well as mysterious movement, emotional suspense and uncanny detail. Fewer still are honored with extensive museum retrospectives that do these worlds full immersive justice, allowing devotees and neophytes alike to grasp the essence of their achievement and its evolution, strengths and weaknesses all.

But this is what the Museum of Modern Art has accomplished for the elaborate puppet-centered parallel universe brought forth by the experimental animators known as the Quay Brothers.

Terry Gilliam Interview | The Talks

Mr. Gilliam, you’ve been given the nickname “Captain Chaos” because of all the things that have gone wrong on your film sets. Do you need chaos on set to be creative?

(Laughs) It isn’t really that. I don’t want chaos, I actually want order. I really want it ordered very well and I want to surround myself with really well organized people so that when we’re on the set and an idea comes in we can play with it because we’ve got a really good structure. So it’s not chaos. Between me and the actors, or between me and the director of photography, it’s more like, “Oh, what if we did that? Okay, we can do that.” So the organized people think it’s chaos, but it’s not. I just build a structure that’s really solid so even if the lead actor dies, we can finish the film. (Laughs)