Does Lady Luck exist or do you make your own luck?

Carlin Flora in Aeon:

New findings suggest that luck is not a phenomenon that appears exclusively in hindsight, like a hail storm on your wedding day. Nor is it an expression of our desire to see patterns where none exist, like a conviction that your yellow sweater is lucky. The concept of luck is not a myth.

Instead, the studies show, luck can be powered by past good or bad luck, personality and, in a meta-twist, even our own ideas and beliefs about luck itself. Lucky streaks are real, but they are the product of more than just blind fate. Our ideas about luck influence the way we behave in risky situations.

The team then dug deeper to reveal why these streaks were in fact real: it was the bettors’ own doing. As soon as they realised they were winning, they made safer bets, figuring their streaks could not last forever. In other words, they did not believe themselves to have hot hands that would stay hot. A different impulse drove gamblers who lost. Sure that lady luck was due for a visit, they fell for the gambler’s fallacy and made riskier bets. As a result, the winners kept winning (even if the amounts they won were small) and the losers kept losing. Risky bets are less likely to pay off than safe ones. The gamblers changed their behaviours because of their feelings about streaks, which in turn perpetuated those streaks.

Everything I know about a good death I learned from my cat

Elizabeth Lopatto in The Verge

She’s clawed out two years; I’d like longer, but that’s not in the cards.

And this is where I feel I have been better served by my vet than many patients are by their doctors: we have had, for the last two years, a continuous conversation about Dottie’s end-of-life plan. No one has ever promised me a cure, or made me hope Dottie will beat cancer.

Demonstrating the pantorouter

Matthias Wandel:

Plenty more about this and other cool projects on his site

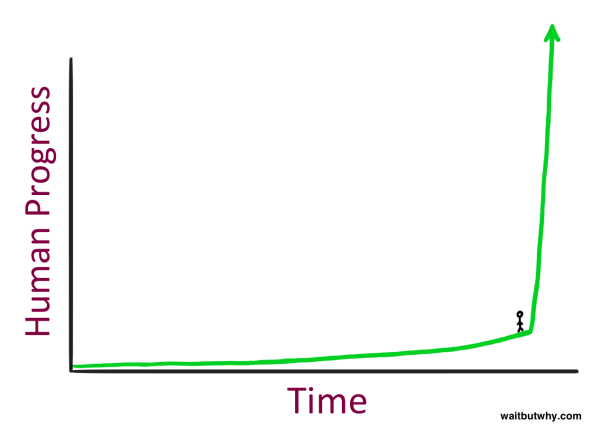

The Artificial Intelligence Revolution

Tim Urban with a decent, if pop-sci, look at the singularity:

What does it feel like to stand here?

Built on Sand: Singapore and the New State of Risk

Joshua Comaroff in Harvard Design Magazine:

In June 2014, drivers crossing the causeway between Singapore and Johor, Malaysia, began to notice something strange. A slender sandbar, which had long stood in the middle of the narrow straits, had started to grow, and was slowly inching toward Singapore. Construction vehicles had arrived, and small barges passed continuously, dumping load after load of sand into the water. Newspapers soon reported that this expanding mound was to become the site of Forest City, a 2,000-hectare high-rise housing development jutting out from the Malaysian port of Tanjung Pelepas. As this privately funded project crept toward Singapore’s national border, the security state doubtlessly felt violated. In response, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong requested that the Malaysian government halt work on the project, and threatened to file a complaint with the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea in Hamburg.

Forest City and its backstory are emblematic of an emerging issue of a transnational order. Less obvious than the increased capital flows across territories is the flow of territory itself. That is, land. Or, more accurately, sand.

In violent times, young Japanese just shrug

Michael Hoffman in The Japan Times

The weekly Shukan Kinyobi discerns a “new fatalism” among young people. Meaning what? A feeling that effort reaps no rewards and so is not worth making; that the world is what it is and cannot be changed — at least not by me, even if I felt like changing it, which I don’t; that luck or inborn talent (which, being inborn, is just luck under another name) determines destiny, excluding most of us from the really good things in life — if they really are good, which they’re not, so to hell with them.

It sounds like despair but it is not. In fact, reports Shukan Kinyobi, young people have never been happier. A paradox indeed — one well worth exploring.

R U There?

Alice Gregory in The New Yorker

In 2011, a young woman named Stephanie Shih was working in New York City at DoSomething.org, a nonprofit that helps young people start volunteer campaigns. Shih was responsible for sending out text messages to teen-agers across the country, alerting them to various altruistic opportunities and encouraging them to become involved in their local communities: running food drives, organizing support groups, getting their cafeterias to recycle more. Silly, prankish responses were not uncommon, but neither were messages of enthusiasm and thanks. Then, in August, after six months on the job, Shih received a message that left her close to tears for the rest of the day. “He won’t stop raping me,” it said. “He told me not to tell anyone.” A few hours later, another message came: “R u there?”

Yitang Zhang’s Pursuit of Beauty in Math

Alec Wilkinson in The New Yorker:

The problem that Zhang chose, in 2010, is from number theory, a branch of pure mathematics. Pure mathematics, as opposed to applied mathematics, is done with no practical purposes in mind. It is as close to art and philosophy as it is to engineering. “My result is useless for industry,” Zhang said. The British mathematician G. H. Hardy wrote in 1940 that mathematics is, of “all the arts and sciences, the most austere and the most remote.” Bertrand Russell called it a refuge from “the dreary exile of the actual world.” Hardy believed emphatically in the precise aesthetics of math. A mathematical proof, such as Zhang produced, “should resemble a simple and clear-cut constellation,” he wrote, “not a scattered cluster in the Milky Way.” Edward Frenkel, a math professor at the University of California, Berkeley, says Zhang’s proof has “a renaissance beauty,” meaning that though it is deeply complex, its outlines are easily apprehended. The pursuit of beauty in pure mathematics is a tenet. Last year, neuroscientists in Great Britain discovered that the same part of the brain that is activated by art and music was activated in the brains of mathematicians when they looked at math they regarded as beautiful.

A Most Violent Year | NYC, 1981

A24 and A MOST VIOLENT YEAR present NYC, 1981. An original short documentary featuring stories from one of the most dangerous years on record for New York City.

Why You Should Tell Your Children How Much You Make

Why are so many people so bad with money? Because we treat money as a taboo topic in the home, worse then sex. Here is a good column exploring this:

Ron Lieber in the NYT:

Money is a source of mystery to children. They sense its power, so they ask questions, lots of them, over many years. Why isn’t our house as big as my cousin’s? Why can’t I have a carnivorous plant terrarium? Why should I respect my teachers if they earn only $60,000 per year? (Real question!) Are we poor? Why didn’t you give money to the man who asked you for some? If my sister can have Hello-Kitty-themed Beats by Dre headphones, why won’t you get me the Bluetooth-enabled Lego Mindstorms set? (It’s only $349, and it’s educational, Mom!)

We adults, however, tend to do a miserable job of answering. We push our children’s money questions aside, sometimes telling them that their queries are impolite, or perhaps worrying that they will call out our own financial hypocrisy and errors. Sometimes we respond defensively and viscerally, barking back, “None of your business,” unintentionally teaching our children that the topic is off limits despite its obvious importance. Others want to protect their children from a topic many of us find stressful or baffling: Can’t we keep them innocent of all of this money stuff for just a little bit longer?

Playing with Power

Dillon Markey, an animator for Robot Chicken and PES, modifies a Nintendo Power Glove as the most awesome animation tool ever.

Sebastian Seung’s Quest to Map the Human Brain

Gareth Cook in the NYT:

The race to map the connectome has hardly left the starting line, with only modest funding from the federal government and initial experiments confined to the brains of laboratory animals like fruit flies and mice. But it’s an endeavor heavy with moral and philosophical implications, because to map a human connectome would be, Seung has argued, to capture a person’s very essence: every memory, every skill, every passion. When the brain isn’t wired properly, it can lead to disorders like autism and schizophrenia — “connectopathies” that could be revealed in the map, perhaps suggesting treatments. And if science were to gain the power to record and store connectomes, then it would be natural to speculate, as Seung and others have, that technology might some day enable a recording to play again, thereby reanimating a human consciousness. The mapping of connectomes, its most zealous proponents believe, would confer nothing less than immortality.

This Top-Secret Food Will Change the Way You Eat

Despite the linkbait headline, this is a decent article anyway:

Rowan Jacobsen in Outside:

Brown’s aha moment came in 2009, when the Worldwatch Institute published “Livestock and Climate Change,” which carefully assessed the full contribution to greenhouse-gas emissions (GHGs) of the world’s cattle, buffalo, sheep, goats, camels, horses, pigs, and poultry. An earlier report by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization had pegged that contribution at 18 percent, worse than cars and trucks. That’s shocking enough, but the Worldwatch study’s authors, two analysts from the World Bank, found that the FAO hadn’t taken into account the CO2 breathed out by our 22 billion livestock animals, the forests being felled to make room for pasture and feed crops, or the total impact of the 103 million tons of methane belched into the air by ruminants each year. When everything was tallied up, Worldwatch estimated, livestock were on the hook for 51 percent of GHGs.

That was all Brown needed to hear to put the plant-based McDonald’s back at the top of his agenda. Forget fuel cells. Forget Priuses. If he could topple Meatworld, he thought, he could stop climate change cold.

A new test measures analytical thinking linked to depression, fueling the idea that depression may be a form of adaptation

“Depression has long been seen as nothing but a problem,” says Paul Andrews, an assistant professor of Psychology, Neuroscience & Behaviour at McMaster. “We are asking whether it may actually be a natural adaptation that the brain uses to tackle certain problems. We are seeing more evidence that depression can be a necessary and beneficial adaptation to dealing with major, complex issues that defy easy understanding.”