Things tagged pol:

Somerdale to Skarbimierz

James Meek in London Review of Books:

How to explain Poland’s swing against the European Union? How to explain the election of the Catholic fundamentalist, authoritarian, populist, Eurosceptic Law and Justice Party to rule a booming country that has benefited from more than €130 billion in EU investment in its roads, railways and schools, a country where only a few years after EU accession in 2004 hundreds of foreign factories and distribution centres opened, employing hundreds of thousands of people, a country whose citizens have taken advantage of EU freedom of movement to travel, work and study across the continent in their millions?

Human Theory of the Left

Eliezer Yudkowsky on Facebook, so quoted in it’s entirety here for posterity:

Bryan Caplan’s Simplistic Theory of Left and Right says “The Left is anti-market and the Right is anti-Left”. This theory is half wrong, and will for this reason confuse the Left in particular. It ought to be a clue that if you ask the Left whether they’re anti-market, most of the Left will answer, “Of course not,” whereas if you ask the Right whether they’re anti-Left, they’ll answer “Hell yes we are.” People may understand themselves poorly a lot of the time, but they often know what they hate.

My “Human Theory of the Left” is as follows: The Left holds markets to the same standards as human beings.

Consider a small group of 50 people disconnected from the outside world, as in the world where humans evolved. When you offer somebody fifty carrots for an antelope haunch, that price carries with it a great array of judgments and considerations, like whether that person has done you any favors in the past, and how much effort it took them to hunt the antelope, and how much effort it took you to gather the carrots. If you offer them an unusually generous price, you’d expect them to give good prices in return in the future. A low price is either a status-lowering insult, or carries with it a judgment that the other person already has lower status than you.

And that’s what the Left sees when they look at somebody being paid $8/hour. They don’t see a supply curve, or a demand curve; or a tautology that for every loaf of bread bought there must be a loaf of bread sold, and therefore supply is always and everywhere equal to demand; they don’t see a price as the input to the supply function and demand function which makes their output be equal. They see a judgment about how hard an employee works, and how much they need and deserve.

So of course they hate whatever looks at a poor starving mother and says “$8/hour”. Who wouldn’t?

Ask them and they’ll tell you: They don’t hate markets. They just think that the prices and outcomes aren’t fair, and that tribal action is required for everyone to get together and decide that the prices and outcomes should be fairer.

If this post gets shared outside my own feed, some people will be reading this and wondering why I wouldn’t want prices to be fair.

And they’ll suspect that I must worship the Holy Market and believe its prices to be wise and fair; and that if I object to any regulation it’s because I want the holy, wise and fair Market Price to be undisturbed.

This incidentally is what your non-economist friends hear you saying whenever you use the phrase “efficient markets”. They think you are talking about market prices being, maybe not fair, but the most efficient thing for society; and they’re wondering what you mean by “efficiency”, and who benefits from that, and whether it’s worth it, and whether the goods being produced by all this efficiency are actually flowing to the people making $8/hour.

You reply, “What the hell that is not even remotely anything the efficient markets hypothesis is talking about at all, you’re not even in the right genre of thoughts, the weak form of the EMH says that the supply/demand-intersecting price for a highly-liquid well-traded financial asset is a rational subjective estimate of the expectation of its supply/demand-intersecting price two years later taking into account all public information, because otherwise it would be possible to pump money out of the predictable price changes. The EMH is a descriptive statement about price changes over time, not a normative statement about the relation of asset prices to anything else in the outside world.”

This is not a short paragraph in the standard human ontology.

“So you think that $8/hour wages are efficient?” they say.

“No,” you reply, “that’s just not remotely what the word efficient means at all. The EMH is about price changes, not prices, and it has nothing to do with this. But I do think that $8/hour is balancing the supply function and the demand function for that kind of labor.”

“And you think it’s good for society for these functions to be balanced?” they inquire.

The one is willing to consider the force of the argument they think they’re hearing–that the market is a weird and foreign god which will nonetheless bring us the right benefits if we make it the right sacrifices. But, they respond, is the market god really bringing us these benefits? Aren’t some people getting shafted? Aren’t some people being sacrificed to save others, maybe a lot of people being sacrificed to save a few others, and isn’t that worth the tribe getting together and deciding to change things?

And you clutch your hair and say, “No, you don’t get it, you know the market is doing something important but you don’t understand what that thing is, you think the markets are like arteries carrying goods around and they can get blocked and starve some tissues, and you want to perform surgery on the arteries to unblock them, but actually THE MARKETS ARE RIBOSOMES AND YOU’RE TRYING TO EDIT THE DNA CODE AND EVERYTHING WILL BREAK SIMULTANEOUSLY LIKE IT DID IN VENEZUELA.”

And what they hear you saying is “The markets are wise, and their prices carry wisdom you knoweth not; do you have an arm like the Lord, and can your voice thunder like His?”

Because, they know in their bones, when a corporation pays an employee $8/hour, it means something. It means something about the employer and it says something about what the employer believes about the employee. And if you say “WAIT DON’T MESS WITH THAT” there’s a lot of things you might mean that have short sentences in their ontology: you could mean that you believe $8/hour is the fair price; you could mean you believe the price is unfair but that it’s worth throwing the employees under the bus so that society keeps functioning; you could believe that maybe the market knows something you don’t.

And all of those things, one way or another, are saying that you believe there’s some virtue in that $8/hour price, some virtue transmitted to it by the virtue you think is present within the market that assigns it. And that’s a cruel thing to say to someone getting $8/hour, isn’t it?

Just look at what the market does. How can you believe that it’s wise, or right, or fair?

And they can’t believe that you don’t think that–even though you’ll very loudly tell them you don’t think that–when you are being like “IF YOU WANT THEM TO HAVE MORE MONEY THEN JUST GIVE THEM MONEY BUT FOR GOD’S SAKE DON’T MESS WITH THE NUMBER THAT SAYS 8.”

This by the way is another example of why it’s an important meta-conversational principle to pay a lot of attention to what people say they believe and want, and what they tell you they don’t believe and want. And that if nothing else should give you pause in saying that the Left is anti-market when so many moderate leftists would immediately say “But that’s not what I believe!”

Maybe we’d have an easier time explaining economics if we deleted every appearance of the words “price” and “wage” and substituted “supply-demand equilibrator”. A national $15/hour minimum supply-demand equilibrator sounds a bit more dangerous, doesn’t it? Increase the Earned Income Tax Credit, or better yet use hourly wage subsidies. Establish a land value tax and give the money to poor people, while being careful not to establish new paperwork requirements that exclude busy or struggling people and being careful about phaseout thresholds. Or if you really insist on looking at things in the simplest possible way, then take money away from rich people and give it to poor people. It’ll do less damage than messing with the supply-demand equilibrators.

I feel like I’m at a banquet watching people trying to eat the plates and they’re like “No, no, I understand what food does, you’re just not familiar with the studies showing that eating small amounts of ceramic doesn’t hurt much” and I’m like “If you knew what food does and what the plates do then you would not be TRYING to eat the plates.”

I honestly wonder if we’d have better luck explaining economics if we used the metaphor of a terrifying and incomprehensible alien deity that is kept barely contained by a complicated and humanly meaningless ritual, and that if somebody upsets the ritual prices then It will break loose and all the electrical plants will simultaneously catch fire. Because that probably is the closest translation of the math we believe into a native human ontology.

Want to help the bottom 30%? Don’t scribble over the mad inscriptions that are closest to them, trying to prettify the blood-drawn curves. Mess with any other numbers than those, move money around in any other way than that, because It is standing very near to them already.

People like Bryan Caplan see people in 6000BC wearing animal skins as the native state of affairs without the Market. People like Bryan keep trying to explain how the Market got us away from that, hoping to foster some good feelings about the Market that will lead people to maybe have some respect for its $8/hour figure.

If my Human Theory of the Left is true, then this is exactly the wrong thing to say, and eternally doomed to failure. To praise that which would offer $8/hour to a struggling family, is directly an insult to that family, by the humanly standard codes of honor. If you want people to leave the $8/hour price alone, and you want to make the point about 6000BC, you could maybe try saying, “And that’s what Tekram does if you have no price rituals at all.”

But don’t try to tell them that the Market is good, or wise, or kind. They can see with their own eyes that’s false.

Some good discussion in the comments, including from Caplan.

Federalism in Blue and Red

Are you a liberal that lives in a rich blue state? Do you look down on red states that cut services as they cut taxes? Perhaps you should check your privilege, and read this excellent article by Joshua T. McCabe on fiscal capacity in National Affairs:

In 2012, Republican governor Sam Brownback and the Republican state legislature in Kansas undertook what would soon be characterized as a radical experiment in supply-side economics. Over the following several years, they reduced the state’s progressive income tax from a top rate of 6.45% down to 4.6% and essentially raised the state’s sales tax from 5.7% to 6.5%. Grover Norquist and Art Laffer were ecstatic while liberals predicted gloom and doom. Five years later, as revenues plunged and the legislature scrambled to find enough money to fund schools and basic services, liberal pundits around the country let out a collective “I told you so.”

Meanwhile, few people noticed that analogous changes were underway in true-blue Massachusetts. In 2009, Democratic governor Deval Patrick and the Democratic state legislature likewise raised the state’s sales tax from 5% to 6.25%. Over the following several years, that same legislature — but with Republican governor Charlie Baker — reduced the state’s flat income tax from 5.3% to 5.1%. Despite strikingly similar shifts in its tax structure, Massachusetts received essentially no praise from supply-side evangelists or condemnation from liberal pundits. More important, no budget crisis followed. What explains these divergent outcomes following similar tax reforms?

Libertarian Social Engineering

Jason Kuznicki at Cato Unbound:

To my mind there are two ways to do libertarian activism.

One approach is easy, deeply satisfying, and - at least on our current margin - it’s basically ineffective. The other approach is difficult, usually thankless, and - I dare say it - revolutionary when it works.

Let’s call the first way libertarian moralizing. We know it by what it aims to produce: The intended product is more libertarians. Eventually we’ll persuade everyone, or at least enough of everyone, and then we’ll change the world.

[…]

To pick a completely incendiary name, I will call this second type of activism libertarian social engineering. By this I mean the deliberate attempt to create, on an incremental, case-by-case basis, the new, voluntary institutions and practices that a society would need if it were to become significantly more private, more decentralized, and more free. I mean here institutions like cryptocurrency, which is already well known; private institutions of assurance and trust in consumer satisfaction and safety; and Alexander Tabarrok’s idea of the Dominant Assurance Contract, which is exceptionally obscure, but which stands to my mind a fair chance of making almost all state action obsolete.

How American Politics Went Insane

Jonathan Rauch in The Alantic:

Chaos syndrome is a chronic decline in the political system’s capacity for self-organization. It begins with the weakening of the institutions and brokers—political parties, career politicians, and congressional leaders and committees—that have historically held politicians accountable to one another and prevented everyone in the system from pursuing naked self-interest all the time. As these intermediaries’ influence fades, politicians, activists, and voters all become more individualistic and unaccountable. The system atomizes. Chaos becomes the new normal—both in campaigns and in the government itself.

Our intricate, informal system of political intermediation, which took many decades to build, did not commit suicide or die of old age; we reformed it to death. For decades, well-meaning political reformers have attacked intermediaries as corrupt, undemocratic, unnecessary, or (usually) all of the above. Americans have been busy demonizing and disempowering political professionals and parties, which is like spending decades abusing and attacking your own immune system. Eventually, you will get sick.

Not about directly about Tump, written early last year. Pointing out a lot of the cronyism and other regressive structures in politics may have helped the whole system function better. But which direction forward, change our political system, or go back to how it was?

The Anarchist in the Woodshop

Daniel D. Clausen discusses Christopher Schwarz’s work at Lost Art Press:

[The Anarchist’s Design Book] explains, again in narrative form, how to make that kind of simple furniture. With more or less the same basic set of flea market tools in the Anarchist’s Tool Chest, along with a willingness to try, experiment, fail, and try again, Schwarz shows that most people can turn out simple, functional furniture. And it will be better made than what is available flat packed from local box stores, and at a fraction of the price of antiques or what handmade furniture costs. Since crafts people have to make a living building something like a chair a week, if they are quick, that sort of production will never be democratically available. It is cost prohibitive for all but the wealthy, and always will be. (This critique, also leveled at William Morris’s Arts and Crafts movement—that the laborers were making furniture for the rich and thus failing at the Marxist goal of revolution—has never struck me as very damning. There has to be some mechanism to get money from where the money currently is, and we ought to be forgiven if we prefer this one to violence.)

The larger political argument in these “anarchist” books is that in a society structured by late consumer capitalism, we’ve all sold our birthright to making things for the bowl of pottage that is IKEA bookshelves and meaninglessness. It’s an appealing argument for direct action, not just in politics, but in daily material life.

The surprise success of Schwartz’s books prompts some questions: What conditions is Lost Art Press responding to? And why has this response been so successful?

The conditions, obviously, are the same ones that suffuse our political moment. Sit down to actually read Karl Marx and it will be difficult not to grant that his analysis of the conditions of capitalism, if not his rather nebulous prescriptions, are prescient. His labor theory of value is appealing, especially to those who have skill in making things. The concentration of capital, high barriers to entry, and economies of scale with diminishing returns all work against the “petite bourgeois” craftsman.

A New Progressive Federalism

The new dean of Yale Law has some smart things to say about federalism:

Heather Gerken in Democracy:

Progressives are deeply skeptical of federalism, and with good reason. States’ rights have been invoked to defend some of the most despicable institutions in American history, most notably slavery and Jim Crow. Many think “federalism” is just a code word for letting racists be racist. Progressives also associate federalism—and its less prominent companion, localism, which simply means decentralization within a state—with parochialism and the suppression of dissent. They thus look to national power, particularly the First and Fourteenth Amendments, to protect racial minorities and dissenters from threats posed at the local level.

But it is a mistake to equate federalism’s past with its future. State and local governments have become sites of empowerment for racial minorities and dissenters, the groups that progressives believe have the most to fear from decentralization. In fact, racial minorities and dissenters can wield more electoral power at the local level than they do at the national. And while minorities cannot dictate policy outcomes at the national level, they can rule at the state and local level. Racial minorities and dissenters are using that electoral muscle to protect themselves from marginalization and promote their own agendas.

Also in Vox:

Federalism doesn’t have a political valence. These days it’s an extraordinarily powerful weapon in politics for the left and the right, and it doesn’t have to be your father’s (or grandfather’s) federalism. It can be a source of progressive resistance — against President’s Trump’s policies, for example — and, far more importantly, a source for compromise and change between the left and the right. It’s time liberals took notice.

Staying true to principle in the age of Trump

Ilya Somin in the WaPo:

Wall Street Journal columnist Bret Stephens, a prominent conservative opponent of Trump, recently noted that he is now more popular on the left than in the past, but despised by many of his former fans on the right:

Watching this process unfold has been particularly painful for me as a conservative columnist. I find myself in the awkward position of having recently become popular among some of my liberal peers—precisely because I haven’t changed my opinions about anything.

Won’t directly apply to many of you, being liberals. But, please read this well written mini essay about the detrimental effects of partisan bias, and reflect on it now, when it doesn’t apply, so that later when it does perhaps you can be a better participant, holding to your values no matter who is leading your team.

Under Trump, red states are finally going to be able to turn themselves into poor, unhealthy paradises

Ignore the dumb headline, and stay for this by Steven Pearlstein in The Washington Post:

After all, if Republicans cut taxes — in particular, taxes on investment income — then the biggest winners are going to be the residents of Democratic states where incomes, and thus income taxes, are significantly higher. Governors and legislatures in those states — home to roughly half of all Americans — will now have the financial headroom to raise state income and business taxes by as much as the federal government cuts them — and use the additional revenue to replace all the federal services and benefits that Republicans have vowed to cut.

and think again about how you can move your government more local, and less federal, thanks to republicans.

Some thoughts on the election

I see people responding to the widespread despair and fear on social media with a positive message of strength and unity. Thank you to these people for responding in a positive fashion, and looking for what we can do to improve our world.

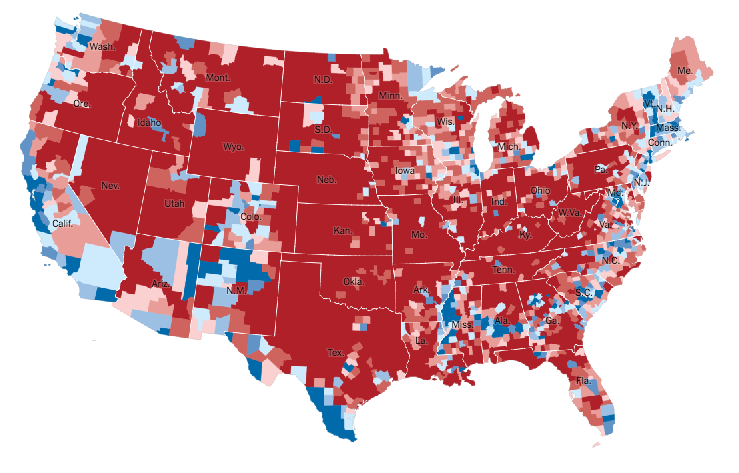

However I personally disagree with the idea of ‘unity’ on a national level being a solution. Take a look at this:

As it was in 2008 and ‘12, the map shows not red and blue states, as the media (due to the electoral college) talk about, but blue cities, and red rural areas. We should be starting to accept that there is not one America, there are two, and that this is ok. I talk frequently about ‘foot voting’, which is the idea that people can express their political preferences by moving to places that are are a better match for them. This has been happening for a while here, and around the world, younger more educated and liberal people are moving to the cities. When they join together in these cities, they change the cites to be closer to their ideal, through the local political process.

So, what should be done about our federal government? Which does have a large impact on us, even those of us in the cities? Well, I believe that a better result for ‘America’ as a whole, and certainly the cities, would be to reduce the power of the national government, to allow cities to diversify, and provide various options for people to vote with their feet. I provide several links talking about this idea in comments to this post below.

Does this mean we are ‘abandoning’ the poor folks in red areas to their terrible fate? No. I have seen some very disappointing articles linked on social media about how third party voters are operating out of white privilege, etc. If we only were at risk of the ‘consequences’ of a Trump presidency we couldn’t vote for anyone but Clinton. In my mind this is exactly the attitude that has gotten us here. That we only have two choices, and we all have to fall in line with one or the other, due to how scary the other side is! The fact of the matter is that to a large extent already, LGBT, people of color and others are already refugees from the red areas. Is this fair? That people should have to leave their houses, families, etc to go to the cities to be safe/express themselves? No of course not. I believe that everyone should respect each other for their beliefs, and be able to live free wherever they are. However this is not reality, and though I hope it will be reality in the future, it will surely be a slow process. How will this process take place? I believe it will be through competition between the cities and the rest of the world. This is how progress has always been made, people that believe in a better life going to a new area, making it theirs, and proving that it is a better way. See also my separate comment below about the rights of ‘red people’ to live as they please. (‘Red people’ of course being a label for people who voted for Trump, red on the map, nothing further is meant by the term)

So, we should work on unity at a local level. Act to make this city the best it can be. Welcome the refugees, provide them safety and a hope for a better future. And if you agree with me about an idea for a better world being a less powerful federal government, work to provide open immigration into your city from the rest of the country as well as the world. Will life here in Seattle become less safe for the people Trump attacked in his speeches, and threatens to do in in policies? I hope not! I hope that we can prevent that, but if it does seem to be happening here, let us gather together and fight it. And even Seattle today (yesterday) as we all know is nowhere near a safe place yet for marginalized people, there is much work still to be done here already.

Footnotes:

Freedom of red folks to live as they want to: The flip side of this, is to try and think about what the red areas are asking for. They went out and voted for Trump for a reason, their own reasons, and who are we to say that they are wrong. Trump seems to me to be a misogynist, and a dangerous person to women. I have a reaction that I should protect all the women of America by voting against him, to prevent him from coming to power. But, 62% of non-college educated white women voted for Trump. By voting against him I actually tried to overrule their stated wishes! I don’t believe in forcing my views on people, and a national election is just that: Me trying to force my views on a whole lot of people who don’t agree with me. I would much rather people in red areas that voted for the policies they desire be allowed to have them, even if the election had gone the other way!

Cities as a term: A city is currently the example of a progressive place in America, and also seems to me to be the future, for economical, cultural, and environmental reasons. However, I do not mean that rural places can’t also be progressive, or that rural places should not be able to take autonomy in a political sense. So I use cities here as a term to mean a self governed group of people. I hope that other places will also be able to self govern if we set up a system of government that would allow it.

Unity locally and tolerance: So what of those people who voted red right next to us, our neighbors and family, etc.? I think as progressive people, we already are aware of the value of inclusion and respect, but these trying times ahead will of course be challenging. They have “won” our national election, and we will have to forgive them some gloating, but do not need to accept their strategic attempts to take the national position of strength and use it locally. Respect, but not passivity!

Another view of the two Americas from the NYT

And a great counterpoint to the conventional narrative from WaPo called Election maps are telling you big lies about small things. Which I feel mostly reinforces what I say above.

Voting with Feet vs. Voting with Ballots

The decisions we make in the voting booth tend to be less informed and less decisive than the votes we cast with our feet. Ilya Somin, author of Democracy and Political Ignorance, explains.

Democracy and Political Ignorance: Why Smaller Government Is Smarter

Ilya Somin’s Democracy and Political Ignorance has profoundly influenced libertarian thinking about voters and elections. More generally, the 2016 primary season has satisfied few and left the electorate choosing between two highly disliked presidential candidates.

Also, his talk at Harvard Kennedy School.

Possible presidential spoiler Gary Johnson speaks to The Times editorial board about siphoning votes from Hillary Clinton

This is two former Republican governors having gotten re-elected in heavily blue states, so what’s that animal? What makes up that animal? So, in myself and Bill Weld’s case, that’s being fiscally conservative and socially liberal. We don’t care what you are socially as long as you don’t force it on others. The third unique leg on the stool is to really be skeptical about our military interventions and the fact that these military interventions have led to the unintended consequence of things being made worse, not better. Rule the world with free trade, rule the world with diplomacy. So free trade, lower taxes, smaller government, but recognizing that government does have a role and choice. Always coming down on the side of choice when it comes down to you and I as individuals. Those choices that don’t put others in harm’s way.

Preliminary thoughts on the Apple iPhone order in the San Bernardino case: Part 3, the policy question

Orin Kerr in The Volokh Conspiracy:

In this post, the third in a series, I want to discuss what I think is the policy question at the heart of the Apple case about opening the San Bernardino iPhone. The question is, what is the optimal amount of physical box security? It’s a question we’ve never asked before because we haven’t lived in a world where a lot of physical box security was possible. Computers and cellphones change that, raising for the first time the question of how much security is ideal.

A Message to Our Customers

Tim Cook at apple.com:

The United States government has demanded that Apple take an unprecedented step which threatens the security of our customers. We oppose this order, which has implications far beyond the legal case at hand.

This moment calls for public discussion, and we want our customers and people around the country to understand what is at stake.

About time a corporation stood up, the telecoms sure haven’t, so Apple took on the role, and now have the opportunity to make a needed stand.

Judge to DOJ: Not All Writs

And Andrew Crocker at the EFF explains why the goverment is overreaching with the use of All Writs:

Reengineering iOS and breaking any number of Apple’s promises to its customers is the definition of an unreasonable burden. As the Ninth Circuit put it in a case interpreting technical assistance in a different context, private companies’ obligations to assist the government have “not extended to circumstances in which there is a complete disruption of a service they offer to a customer as part of their business.” What’s more, such an order would be unconstitutional. Code is speech, and forcing Apple to push backdoored updates would constitute “compelled speech” in violation of the First Amendment. It would raise Fourth and Fifth Amendment issues as well. Most important, Apple’s choice to offer device encryption controlled entirely by the user is both entirely legal and in line with the expert consensus on security best practices. It would be extremely wrong-headed for Congress to require third-party access to encrypted devices, but unless it does, Apple can’t be forced to do so under the All Writs Act.

Via darringfireball

Capitol Bells

And in reference to the previous post, here is an app that pokes a bit at the representative vs. direct democracy:

Capitol Bells lets you cast your vote for upcoming bills, and informs you when your elected representative votes for, or against, or not at all.

Of course the problem isn’t so much the voting, much more the understanding the bills. I have some ideas on this front, but need some more time to think them through, and would be a huge project to build …

Why real-world governments don’t have the consent of the governed – and why it matters

Ilya Somin at The Volokh Conspiracy:

The Declaration of Independence famously states that governments derive “their just powers from the consent of the governed.” But, sadly, this is almost never the case in the real world. If it is indeed true, as Abraham Lincoln famously put it, that “no man is good enough to govern another man without that other’s consent,” that principle has more radical implications than Lincoln probably intended. Few if any of those who wield government power measure up to that lofty standard.

A fantastic overvew of some things I feel very strongly about. And his conclusion is exactly the same as mine:

The nonconsensual nature of most government policies also strengthens the case for devolving power to regional and local authorities in order to increase the number of issues on which citizens can “vote with their feet” and thereby exercise at least some degree of meaningful consent.

The Case of the Missing Hong Kong Book Publishers

Jiayang Fan in The New Yorker:

When a politically problematic figure disappears—or is disappeared—in China, a dark uneasiness falls, though usually accompanied by a glum sense of the inevitable. This is the cost of living within an authoritarian regime with diminishing patience for deviance. For a breather from such oppressive strictures, one might hop across the border to Hong Kong, where the policy of “one country, two systems” guarantees the freedom of speech and of the press, under the former British colony’s Basic Law, its own mini-Constitution. That refuge had seemed reasonably dependable, at least until a week ago, when Lee Bo became the fifth member of a Hong Kong-based publishing house specializing in provocative tomes about Beijing leaders to vanish mysteriously, not on a trip to the mainland but from his own home city, Hong Kong.