Things tagged science:

Is it fair to say that most social programmes don't work?

Lots of government and charity programmes aim to improve education, health, unemployment and so on. How many of these efforts work?

The vast majority of social programs and services have not yet been rigorously evaluated, and…of those that have been rigorously evaluated, most (perhaps 75% or more), including those backed by expert opinion and less-rigorous studies, turn out to produce small or no effects, and, in some cases negative effects.

This estimate was made by David Anderson in 2008 on GiveWell’s blog. At that time, he was Assistant Director of the Coalition for Evidence-Based Policy.

This has become a widely-quoted estimate, especially in the effective altruism community, and often gets simplified to “most social programmes don’t work”. But the estimate is almost ten years old, so we decided to investigate further. We spoke to Anderson again, as well as Eva Vivalt, the founder of AidGrade, and Danielle Mason, the Head of Research at the Education Endowment Foundation.

We concluded that the original estimate is reasonable, but that there are many important complications. It seems misleading to say that “most social programmes don’t work” without further clarification, but it’s true that by focusing on evidence-based methods you can have a significantly greater impact.

Minimum Wage and Restaurant Hygiene Violation: Evidence from Food Establishments in Seattle by Subir Chakrabarti, Srikant Devaraj, Pankaj Patel

No free lunch, hygiene edition:

We assess the effects of rise in minimum wages on hygiene violation scores in food service establishments. Using a difference-in-difference analysis on hygiene rating of food establishments in Seattle [where minimum wage increased annually between 2010 and 2013] as the treated group and from New York City [minimum wage was constant] as the control group, we find an increase in real minimum wage by $0.10 increased total hygiene violation scores by 11.45 percent. Consistent with our theoretical model, an increase in minimum wage in Seattle has no influence in more severe (red) violations, and a significant increase in less severe (blue) violations. Our findings are consistent while using an alternate control group - Bellevue City, King County, located near Seattle.

Hanging On For Dear Life

At Biophilia:

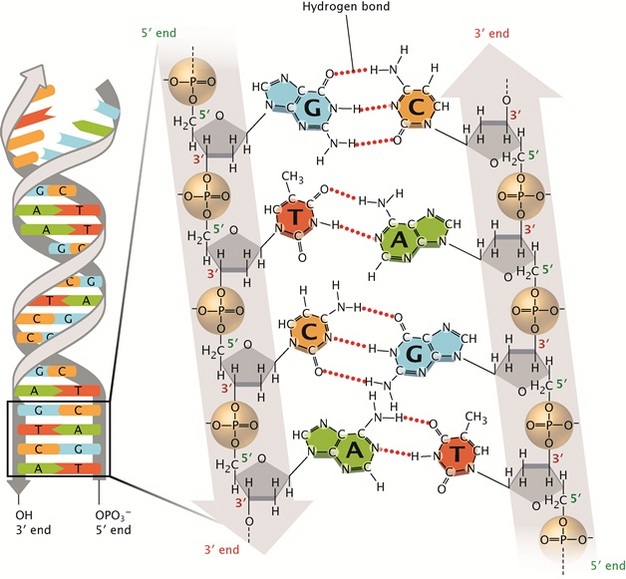

At the very heart of our hereditary and developmental lives is DNA synthesis- replication that copies one duplex into two. But each beautiful, classic DNA duplex has two strands, each of which needs to be copied. Not only that, but those two strands go in opposite directions. The one is the complement, or anti-sense, of the other one, and in chemical terms heads the other way. This creates a significant problem, since the overall direction of replication can only go one way- the direction of the fork where the parental duplex splits into two.

What the Dust in Your House Says About You

Emily Anthes in The New Yorker:

Each bit of dust is a microhistory of your life,” Rob Dunn, a biologist at North Carolina State University, told me recently. For the past four years, Dunn and two of his colleagues—Noah Fierer, a microbial ecologist at the University of Colorado Boulder, and Holly Menninger, the director of public science at N.C. State—have been deciphering these histories, investigating the microorganisms in our dust and how their lives are intertwined with our own.

Most of our microscopic roommates are unlikely to present a real threat; many species of bacteria, scientists now know, are crucial partners in maintaining our health. “We’re surrounded by microbes all the time, and that’s not a bad thing,” Fierer said. In the next phase of their research, he and Dunn hope to identify connections between a home’s microscopic inhabitants and the health of its human ones. And there are likely to be more findings lurking in the dust that the volunteers already collected. How does the use of antimicrobial cleaning products alter a home’s profile? Is there a link between our genomes and the species that occupy our homes? There’s far more data than the scientists can analyze themselves, so they have posted it all online; members of the public can download the complete data set and hunt for new correlations and patterns.

You Can't Walk in a Straight Line—And That's Great for VR

Sarah Zhang in Wired:

Humans, quite simply, suck at walking in straight lines: Give a man a blindfold, and he will walk around in circles. In virtual reality, though, this failing becomes very convenient. People are so bad at knowing where they are in space that subtle visual cues can trick them into believing they’re exploring a huge area when they’ve never left the room—a process called redirected walking.

With VR technology getting ever better, people could one day explore immersive virtual spaces—like buildings or even whole cities—on foot in head-mounted displays. But it’s not very immersive if you end up smacking into a real-life wall. “This problem of how you move around when in VR is one of the big unsolved problems of the VR community,” says Evan Suma, a computer scientist at the University of Southern California.

That’s where redirected walking comes in. People don’t really notice, it turns out, if you increase or decrease the virtual distance they had to walk by 26 percent or 14 percent, respectively. Or shift the virtual room so they see their path as straight when their real path is curved. Or turn the room up to 49 percent more or 20 percent less than the rotation of their heads.

Doubts Raised About Breast Cancer Treatments for Early Stage Condition

Gina Kolata in the NYT:

As many as 60,000 American women each year are told they have a very early stage of breast cancer — Stage 0, as it is commonly known — a possible precursor to what could be a deadly tumor. And almost every one of the women has either a lumpectomy or a mastectomy, and often a double mastectomy, removing a healthy breast as well.

Yet it now appears that treatment may make no difference in their outcomes. Patients with this condition had close to the same likelihood of dying of breast cancer as women in the general population.

The curious case of whistled languages and their lack of left-brain dominance

Cathleen O’Grady in Ars:

Whistled Turkish is a non-conformist. Most obviously, it bucks the normal language trend of using consonants and vowels, opting instead for a bird-like whistle. But more importantly, it departs from other language forms in a more fundamental respect: it’s processed differently by the brain.

Language is usually processed asymmetrically by the brain. The left hemisphere does the heavy lifting, regardless of whether the language in question is spoken, written, or signed. Whistled Turkish is the first exception to this rule, according to a paper in this week’s issue of Current Biology. There’s evidence that both hemispheres pitch in about the same amount of effort when processing the whistled words.

This evidence could contribute to our general understanding of how the brain works by answering some of the many mysteries about how and why we have asymmetrical processing. And perhaps very far down the road, this research could help stroke sufferers regain some of their lost communicative skills.

The Work We Do While We Sleep

For a long time, sleep’s apparent uselessness amused even the scientists who studied it. The Harvard sleep researcher Robert Stickgold has recalled his former collaborator J. Allan Hobson joking that the only known function of sleep was to cure sleepiness. In a 2006 review of the explanations researchers had proposed for sleep, Marcos Frank, a neuroscientist then working at the University of Pennsylvania (he is now at WSU Spokane) concluded that the evidence for sleep’s putative effects on cognition was “weak or equivocal.”

But in the past decade, and even the past year, the mystery has seemed to be abating. In a series of conversations with sleep scientists this May, I was offered a glimpse of converging lines of inquiry that are shedding light on why such a significant part of our lives is spent lying inert, with our eyes closed, not doing anything that seems particularly meaningful or relevant to, well, anything.

Can we reverse the ageing process by putting young blood into older people?

Ian Sample at The Guardian:

A series of experiments has produced incredible results by giving young blood to old mice. Now the findings are being tested on humans.

The Misleading War on GMOs: The Food Is Safe. The Rhetoric Is Dangerous.

Anyone paying attention knows this already, but here is an absolutely brutal article calling them out in detail.

William Saletan at Slate:

The war against genetically modified organisms is full of fearmongering, errors, and fraud. Labeling them will not make you safer.

The Really Big One

Fantastic science writing, don’t miss this.

Kathryn Schulz in The New Yorker:

In the end, the magnitude-9.0 Tohoku earthquake and subsequent tsunami killed more than eighteen thousand people, devastated northeast Japan, triggered the meltdown at the Fukushima power plant, and cost an estimated two hundred and twenty billion dollars. The shaking earlier in the week turned out to be the foreshocks of the largest earthquake in the nation’s recorded history. But for Chris Goldfinger, a paleoseismologist at Oregon State University and one of the world’s leading experts on a little-known fault line, the main quake was itself a kind of foreshock: a preview of another earthquake still to come.

Do atoms going through a double slit ‘know’ if they are being observed?

Does a massive quantum particle – such as an atom – in a double-slit experiment behave differently depending on when it is observed? John Wheeler’s famous “delayed choice” Gedankenexperiment asked this question in 1978, and the answer has now been experimentally realized with massive particles for the first time.

It’s Not a ‘Stream’ of Consciousness

Gregory Hickok in The New York Times:

In 1890, the American psychologist William James famously likened our conscious experience to the flow of a stream. “A ‘river’ or a ‘stream’ are the metaphors by which it is most naturally described,” he wrote. “In talking of it hereafter, let’s call it the stream of thought, consciousness, or subjective life.”

While there is no disputing the aptness of this metaphor in capturing our subjective experience of the world, recent research has shown that the “stream” of consciousness is, in fact, an illusion. We actually perceive the world in rhythmic pulses rather than as a continuous flow.

Apollo 13, We Have a Solution

Stephen Cass in Spectrum:

“Houston, we’ve had a problem.”

Thirty-five years ago today, these words marked the start of a crisis that nearly killed three astronauts in outer space. In the four days that followed, the world was transfixed as the crew of Apollo 13–Jim Lovell, Fred Haise, and Jack Swigert–fought cold, fatigue, and uncertainty to bring their crippled spacecraft home.

But the crew had an angel on their shoulders–in fact thousands of them–in the form of the flight controllers of NASA’s mission control and supporting engineers scattered across the United States.

Feynman: Fire FUN TO IMAGINE

Physicist Richard Feynman talks more about jiggling atoms and heat, and about what fire is

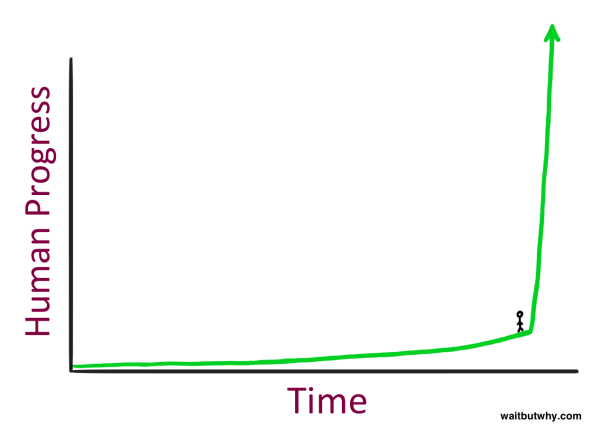

The Artificial Intelligence Revolution

Tim Urban with a decent, if pop-sci, look at the singularity:

What does it feel like to stand here?

Sebastian Seung’s Quest to Map the Human Brain

Gareth Cook in the NYT:

The race to map the connectome has hardly left the starting line, with only modest funding from the federal government and initial experiments confined to the brains of laboratory animals like fruit flies and mice. But it’s an endeavor heavy with moral and philosophical implications, because to map a human connectome would be, Seung has argued, to capture a person’s very essence: every memory, every skill, every passion. When the brain isn’t wired properly, it can lead to disorders like autism and schizophrenia — “connectopathies” that could be revealed in the map, perhaps suggesting treatments. And if science were to gain the power to record and store connectomes, then it would be natural to speculate, as Seung and others have, that technology might some day enable a recording to play again, thereby reanimating a human consciousness. The mapping of connectomes, its most zealous proponents believe, would confer nothing less than immortality.

Why String Theory Still Offers Hope We Can Unify Physics

Brian Greene in Smithsonian Magazine:

In October 1984 I arrived at Oxford University, trailing a large steamer trunk containing a couple of changes of clothing and about five dozen textbooks. I had a freshly minted bachelor’s degree in physics from Harvard, and I was raring to launch into graduate study. But within a couple of weeks, the more advanced students had sucked the wind from my sails. Change fields now while you still can, many said. There’s nothing happening in fundamental physics.

Then, just a couple of months later, the prestigious (if tamely titled) journal Physics Letters B published an article that ignited the first superstring revolution, a sweeping movement that inspired thousands of physicists worldwide to drop their research in progress and chase Einstein’s long-sought dream of a unified theory. The field was young, the terrain fertile and the atmosphere electric. The only thing I needed to drop was a neophyte’s inhibition to run with the world’s leading physicists. I did. What followed proved to be the most exciting intellectual odyssey of my life.

That was 30 years ago this month, making the moment ripe for taking stock: Is string theory revealing reality’s deep laws? Or, as some detractors have claimed, is it a mathematical mirage that has sidetracked a generation of physicists?